What Is Qi? Types of Qi According to Traditional Chinese Medicine

As a Licensed Acupuncturist, one of the most fascinating lessons in the early part of our education is on Qi and all of the different types of Qi our body requires to function properly. This blog provides a brief overview of what Qi is and what types of Qi are involved in the physiology of our body.

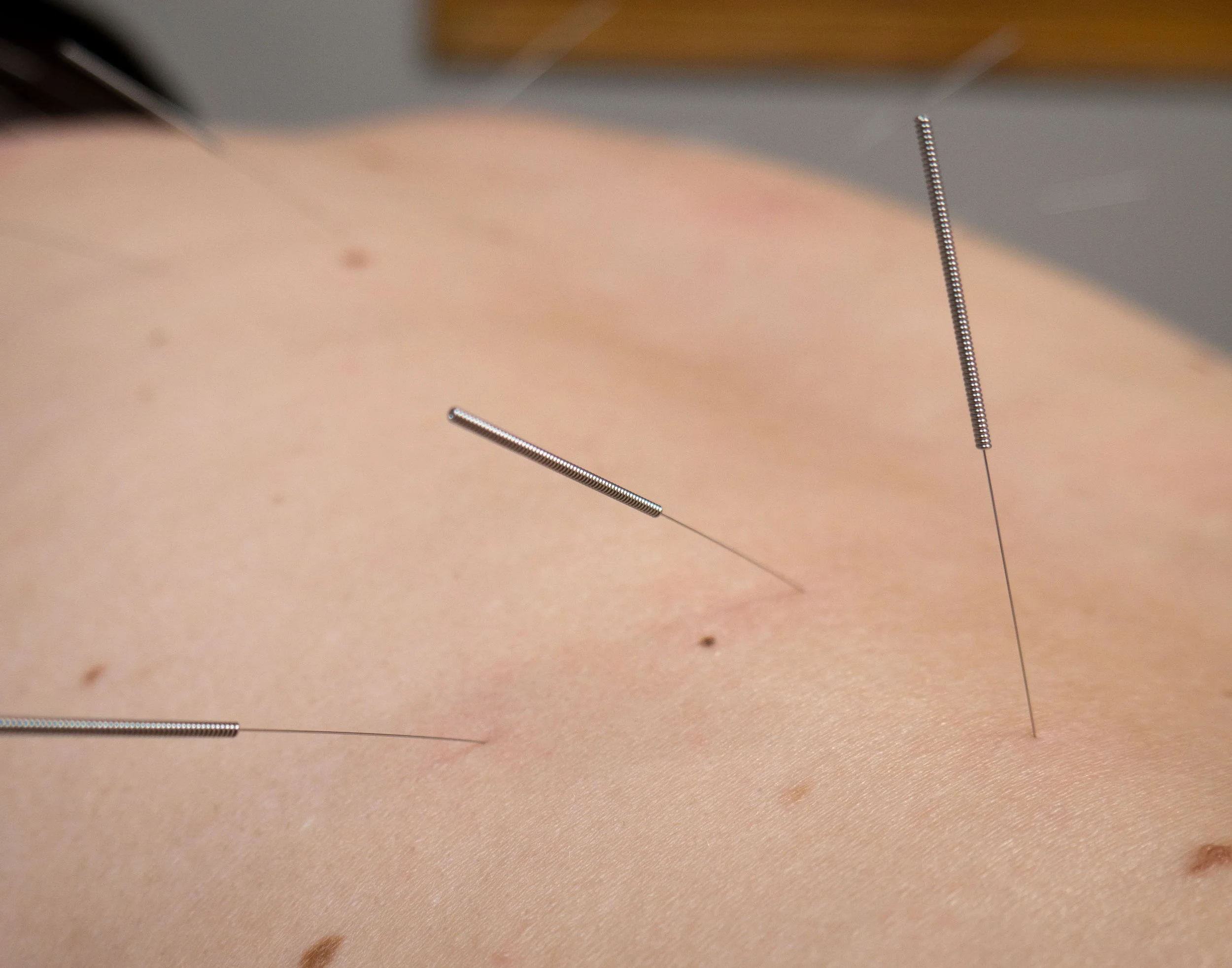

Qi, pronounced ‘Chee’, is a foundational concept in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) representing the vital life force, energy, or “breath” that sustains all living beings and the universe. The Qi flows through pathways known as meridians which are then accessed through acupuncture points.

Qi refers to the dynamic processes that enable movement, transformation, protection, warming, and containment within the body. All physiological activity, including digestion, circulation, respiration, immune defense, and emotional regulation, is understood through Qi. Stable health relies not only on the presence of Qi, but on adequate quantity, proper direction, and harmonious flow of the Qi of our body, mind, and spirit.

The Meaning and Historical Origins of Qi

The concept of Qi originates in classical Chinese philosophy and medicine, with written references dating back more than two thousand years. The traditional Chinese character for Qi, 氣, combines the imagery of vapor rising over rice. This imagery reflects the principle of transformation: Qi is produced when the body’s internal systems are actively transforming food and the air we breathe. Qi is therefore not a static substance, or mere energy, but a functional process that bridges the material and immaterial aspects of physiology and all living things.

In classical texts, Qi is used to explain how the body responds to internal and external change. Rather than isolating organs or symptoms, Qi describes relationships, movement, and coordination. This systems-based perspective remains central to modern TCM, making its understanding of our health fundamentally holistic.

How Qi Is Formed in the Body

Qi is continuously produced through the interaction of several organ systems, each contributing a specific component to the process of how we transform our environment internally and externally through different types of Qi. It is how we, as humans, convert our world into our own physiological functioning and well being.

The Stomach and Spleen are responsible for breaking down food and extracting its usable essence. The Lungs govern respiration and draw in clear Qi from the air. The Kidneys store Jing, or Essence, which provides the foundational support for all Qi production and transformation. Together, these systems ensure that Qi is constantly renewed.

Because Qi formation depends on multiple organs, weakness in digestion (Stomach), respiration (Lungs), or constitutional reserves (Kidneys) can all affect overall vitality. This explains why fatigue, immune weakness, and poor stress tolerance often coexist clinically. TCM does not view these as separate issues, but as different expressions of disrupted Qi production or regulation.

Gu Qi (Food Qi)

Gu Qi, pronounced as ‘goo chee’, is the type of Qi that is formed and derived from our intake of food and drink through the action of the Stomach and Spleen. It represents the initial stage of Qi formation and serves as the material basis for the production of other types of Qi and Blood. After digestion, Gu Qi arises toward the chest, where it combines with Zong Qi, or Air Qi, to form more refined forms of Qi.

From a modern health perspective, Gu Qi is closely related to digestive efficiency, gut health, and nutrient absorption. When Gu Qi is strong, individuals experience steady energy, mental clarity, and stable appetite. When it is weak or improperly transformed, symptoms may include bloating, heaviness, fatigue after meals, sugar cravings, loose stools, or difficulty concentrating. Chronic digestive weakness can therefore have far-reaching effects on overall health and vitality.

Zong Qi (Air Qi)

Zong Qi, pronounced as ‘zong chee’, is formed by the Lungs from the inhaled air we breathe and reflects the body’s capacity to take in, distribute, and utilize oxygen. It descends downward into the body and plays a key role in supporting circulation, metabolism, and immune defense. Zong Qi is not only dependent on lung capacity, but also on posture, breathing patterns, and emotional state (this is why diaphragmatic breathing and breathwork is so important).

In modern terms, Zong Qi relates to respiratory efficiency, oxygen exchange, and nervous system regulation. Chronic stress, grief, shallow breathing, or prolonged sedentary habits can impair Zong Qi, leading to fatigue, chest tightness, frequent respiratory infections, or reduced stamina. Zong Qi combines with Gu Qi to then form Zhong Qi, or Gathering Qi, so any weakness in respiration can cause digestive or circulatory issues according to TCM.

Zhong Qi (Gathering Qi)

Zhong Qi, pronounced as ‘schong chee’, is formed in the chest from the combination of Gu Qi and Zong Qi (food and air). It supports the Heart and Lungs and plays a central role in regulating respiration and circulation. Zhong Qi also influences the strength of the voice, the rhythm of breathing, and the ability to sustain physical activity.

Clinically, Zhong Qi is associated with cardiopulmonary endurance and circulatory efficiency. When Zhong Qi is strong, breathing is deep and regular, circulation is smooth, and physical exertion is well tolerated. When it is weak, individuals may experience shortness of breath, a weak or soft voice, palpitations, chest discomfort, or fatigue with mild activity. Zhong Qi also helps regulate the upward and downward movement of Qi throughout the body, making it essential for overall coordination, especially during activity. Clinically, shortness of breath, weak voice, or other lung conditions are often connected to the Spleen/Stomach and Lungs/Large Intestine paired organ systems because of this relationship.

Ying Qi (Nutritive Qi)

Ying Qi, pronounced as ‘yeeng chee’, is a refined form of Qi derived from Gu Qi that circulates within the blood vessels and channels alongside the Blood. Its primary role is nourishment. Ying Qi supports the internal organs, muscles, skin and mental activity, and is most active during rest and sleep when the body repairs and restores itself.

In modern health contexts, Ying Qi is closely linked to tissue nourishment, hormonal balance, sleep quality, and cognitive function. Deficiency or disruption of Ying Qi may manifest as insomnia, anxiety, poor memory, dry skin, brittle hair, or difficulty recovering from physical or emotional stress. Because Ying Qi is closely tied to Blood, imbalances often present with signs of both Qi and Blood deficiency.

Wei Qi (Defensive Qi)

Wei Qi, pronounced as ‘way chee’, is the body’s defensive Qi and functions as the first line of protection against external pathogens. It is formed from transformed Gu Qi, supported by the Kidneys, and distributed by the Lungs. Unlike Ying Qi, Wei Qi circulates outside the vessels, moving through the skin and muscles. It governs sweating, regulates body temperature, and protects against environmental influences such as wind, cold, heat, and dampness.

From a modern perspective, Wei Qi corresponds to immune resilience, barrier function, and autonomic nervous system balance. Weak Wei Qi may present as frequent colds, allergies, spontaneous sweating, sensitivity to temperature changes, or difficulty adapting to stress. Strengthening Wei Qi is often a key focus in preventive care.

Yuan Qi (Original Qi)

Yuan Qi, pronounced as ‘yoo-wan chee’, originates in the Kidneys and is rooted in Jing, the Essence inherited at birth. It serves as the fundamental driving force behind all physiological activity and supports growth, development, reproduction, and long-term vitality. Yuan Qi also acts as the catalyst that enables other types of Qi to function effectively.

In contemporary health terms, Yuan Qi relates to constitutional strength, endocrine balance, recovery capacity, and aging. While it is partly inherited, lifestyle factors such as chronic stress, overwork, poor sleep, and prolonged illness can deplete Yuan Qi over time. Preserving Yuan Qi is therefore central to longevity and sustainable health.

Qi in Modern Health

Many modern health concerns arise from chronic imbalances over time rather than acute disease. Fatigue, hormonal imbalances, digestive disorders, immune dysfunction, stress-related illness, and emotional dysregulation are often interconnected. The understanding of Qi provides a framework for understanding these patterns as expressions of disrupted regulation rather than isolated symptoms and makes Traditional Chinese Medicine fundamentally holistic.

Acupuncture and other Traditional Chinese Medicine therapies aim to strengthen deficient Qi, regulate stagnation, and correct improper direction of flow. By addressing these underlying patterns, treatment supports the body’s inherent capacity to maintain balance and adapt to ongoing demands.

Qi is not a metaphor or symbolic idea within Traditional Chinese Medicine. It is a functional model describing how life operates at every level of the body. Understanding the different types of Qi allows for a deeper appreciation of how digestion, respiration, immunity, circulation, and emotional health are interconnected. Within this framework, health is defined not simply as the absence of disease, but as the presence of resilient, well-regulated, and harmonious Qi. When you receive acupuncture from a Licensed Acupuncturist, the acupuncture points are reservoirs of Qi where Qi is most abundant so that the proper flow and direction of Qi can be restored to promote harmony in the body, mind, and spirit.